The Asexual K-Drama Geek Reviews: Squid Game

Brief mentions of minor spoilers

Brief discussions of some of the violent or gory elements of the show, as well as slight mentions of other things that might be triggering for some readers.

-------------------------------------

Summary

Although I’m sure most people know the basic premise of Squid

Game by this point, allow me to summarize just in case. The show follows

the story of Seong Gi-hun (played by Lee Jung-jae), a down-on-his-luck man with

a gambling problem. Gi-hun’s life has been marked by bad luck and hardship,

leading to the downtrodden circumstances he finds himself in. Unable to provide

for his daughter, pay back his debts, or live a normal life, things are

beginning to look dire for Gi-hun… until he is approached by a mysterious man

who offers him a shot at winning money for playing children’s games. It seems a

simple enough proposition, if not a slightly strange one – but when he accepts,

he, along with hundreds of other people, find themselves taken to a deserted

island for a sadistic competition.

It soon becomes clear that the games have a deadly

ultimatum: win and you earn an extraordinary sum of money; lose, and you die. Of

the players that survive the first game – a bloody, high-mortality game of Red

Light, Green Light – a majority vote to leave the island and are freed as per

the rules of the game. But many of them, Gi-hun included, realize that life

outside the games is still desolate and they still have very little hope for

things getting better, and thus they voluntarily return to the games in the

hopes they can win the enormous prize. At the same time, a young police officer

begins exploring the reports of this evil game which no one else will believe.

He, however, suspects his own older brother to have vanished as part of a

previous year’s competition, and so he smuggles himself to the island to

investigate while Gi-hun and the others compete.

Although there can only be one winner, the returning players

begin to learn more about each other and soon divide into various factions. One such faction includes Gi-hun, a friend of his from childhood, an elderly man with a terminal

illness, a young North Korean defector trying to earn enough money to get her

family to South Korea, and a worker from Pakistan trying to provide for his

family. Therefore, although the show’s premise is gory and grim, it also

becomes emotionally impactful. Not only do we as viewers become attached to

these characters, but they become attached to each other, and the idea of

losing any of them becomes gut-wrenching.

Each of these characters goes through an arc – some with

more twists and turns than others, of course – and they each get their time to

shine. Heroes and villains alike emerge, both in Gi-hun’s group and among the

players in general, making the entire ensemble cast extremely compelling to

watch. If any one of these main players was even a fraction less well-written

or well-acted, the show as a whole would suffer. But each actor is perfect for

the role, and the show’s creator, writer, and director Hwang Dong-hyuk crafts

brilliant stories for each character. The result is a truly terrifying,

heart-wrenching, and excellent show that has stuck with me, and certainly will

stick with me when season two arrives sometime next year.

My Thoughts/Review

When Squid Game first started gaining traction, I

admit I was somewhat reluctant to watch it. This was largely because, as

mentioned in my previous post, I’m an extremely squeamish person and I knew the

show would be quite gory. It is, of course, and there are definitely scenes

that cross into a territory that I would personally consider gratuitous at

times – scenes that don’t really add anything to the story and which wouldn’t

affect the quality if they weren’t there. In other cases, a plot point is

clearly essential to the story and thus I wouldn’t advocate for it being

removed, but these are scenes that do personally make me uncomfortable, so some

of those scenes were a bit tough to watch. One of the strongest examples of

this is the side plot in which one of the players and several of the guards are

caught running an organ trafficking scheme, harvesting organs from dead players

to sell on the black market. This plot point is important because the discovery

of this leads to an important ripple effect of consequences that affect our

main characters, but I still couldn’t watch those scenes due to some of my own

personal squicks and phobias.

Apart from these things, however, if I can handle Squid

Game, I think most people could – unless, of course, blood, gore, or

violence are deeply uncomfortable and/or triggering for you. The thing that

makes it worthwhile is the characters and the depth of their stories, as well

as the incredible way they are portrayed. None of these characters are

completely innocent, whether in the game or in their lives outside of it, but

there is a realness to all of them that raises the stakes on everything. As the

lead, Gi-hun is of course a good example of this, and we see him run the gambit

of possible states of being – starting off as a pitiful and sometimes cowardly

man, before becoming a good-natured ally to his little group of misfits, and

eventually dabbling in some darker, angrier, or more manipulative things to

stay alive.

But Gi-hun isn’t the only great character in the show. In

last week’s post (a repost from my main blog), I discussed North Korean

defector Kang Sae-byeok, probably my favorite character in the entire show.

Sae-byeok is a stoic, tough character, but she isn’t only that. Right away, we

see the depth of her love for her family, and her willingness to sacrifice

anything if it means she can reunite the family and give them a better life in

South Korea. The show even allows us to feel sympathy for some of the

characters who succumb to the game’s “kill or be killed” mentality,

demonstrating to us not only the horror of the games, but the terrible reality

of a world that makes people that desperate in the first place. These lessons

may sound fairly common or obvious, but the tension of the games and the show’s

edge-of-your-seat moments allow these universal truths to hit even harder.

|

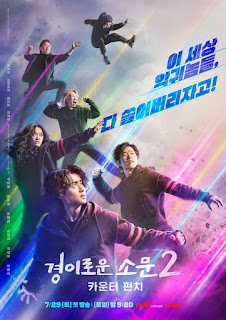

| Image description: From left to right - Cho Sang-woo (played by Park Hae-soo), Seong Gi-hun (played by Lee Jung-jae) and Kang Sae-byeok (played by Jung Ho-yeon) |

To me, Squid Game is an incredible show, and for a while it was my favorite K-Drama. Although it has since been pushed down on my personal list by other shows, it’s still firmly in the top ten for me, in large part because of its characters and the haunting quality of their harrowing journey. For as good as it is, however, it’s not a perfect show, and there are a few elements that I personally find unnecessary or poorly executed. One of those is a common critique I saw made by many people around the time the show came out – that would be the inclusion of the VIPs, first introduced in the episode of the same name. In contrast to the depth of the players in the game, the VIPs – wealthy foreign investors who have been betting on the games and come to watch them in person – are all incredibly flat. Bedecked in golden animal masks to hide their identities and arrayed in strange rooms full of body-painted models used as set dressing, the VIPs are almost cartoonish, presented in a way that feels incongruous with the best parts of the show.

The VIPs, for as strange as they are, aren’t the only

instance of uneven tone in the show. Part of the horror of the games comes from

the fact that they are such innocent concepts dialed up to such sadism, and

when it works, it really works. The visceral contrast of the bright, childlike

rooms where the games take place with the death and destruction wrought within

them is deeply unsettling and effective, leading to a liminal space effect I

imagine even some horror movies would be jealous of. But although this works in

certain games and moments (see: the now-iconic doll that serves as the caller

for Red Light, Green Light, for instance), there are other moments that strike

me as strange in a non-effective and almost immersion breaking way.

For instance, when the Front Man – who oversees the games –

is watching on a monitor while Red Light, Green Light comes to its conclusion, a

cover of Frank Sinatra’s “Fly Me to the Moon” is playing in the background. The

tonal difference of this song playing while several players are eliminated

could be an interesting style choice, but it almost crosses into the absurd

when you consider the song is playing from a sort of electronic marionette show

in the Front Man’s office. There are other strange choices that, rather than

enhance the show’s frightening tone, create an odd mixture of styles in my

opinion, such as a slow-motion shot at the end of one of the later games that seems like it

belongs in The Matrix series.

Other than the VIPs, whose existence is admittedly somewhat

distracting for the show’s final three episodes in which they appear, these

things are mostly just bumps in the road in what is otherwise an incredible

show. But, as a blog whose focus is analyzing K-Dramas from an

asexual/aromantic lens, naturally I want to talk about the show from that

viewpoint too and unpack those plot points in more detail. Like the things mentioned

in this section, these aren’t deal breakers, but they are things I’d like to

highlight as part of the overall package that is Squid Game.

The Aspec Stuff

As I mentioned in my intro, it’s actually kind of ironic to

me that this show is the first K-Drama I saw, not only because it’s very

different from many other K-Dramas, but because it’s also one of the least

aspec (asexual/aromantic spectrum) friendly shows I’ll be covering on this blog,

at least when my own definitions are applied. But at the same time, it might be

somewhat perfect for that same reason. In a way, it serves as a fitting

transition from shows and movies made here in the Western

hemisphere into Korean ones, which I feel are far superior. Although Squid Game is more sexually

explicit than many K-Dramas I’ve watched thus far, it is indeed still quite

mild comparatively when you consider this is a TV-MA show on Netflix, where

usually the temptation (and means) exists to be as sexually explicit as

possible.

In this show, by contrast, there are only two scenes that

are of concern in terms of showing sexual content and/or nudity. The first scene

comes in episode four, during which two of the side characters sneak away to

have sex, part of which is shown on screen. The only thing this scene really

does is reveal the names and motivations of the two side characters,

establishing their tenuous alliance and cementing even further that these two

are dangerous, manipulative, and destructive. In fact, I actually mentioned

this on my regular blog when discussing the show: it’s interesting to me that

the only sexual things depicted in the show are in relation to characters that

are deliberately unpleasant or antagonistic. I’m not saying that sex should

only be portrayed for villains – and there are of course other K-Dramas where

sex is portrayed for protagonists or more sympathetic characters – nor that sex

should be automatically considered bad. What I am saying, however, is that I

find it noteworthy that the main group is not portrayed in this manner at all.

Rather than have any of the main characters getting into these types of

relationships, it’s two characters – the thuggish Jang Deok-su and

unscrupulous conwoman Han Mi-nyeo - who [spoiler alert!] eventually betray one another

anyway.

The other scene that includes nudity once again features an unpleasant character, this time one of the VIPs. The VIPs are distasteful primarily because they bet money on the act of watching people kill and die, and in episode seven, one of them sexually propositions a waiter – who turns out to be the aforementioned police officer in disguise. Nudity is shown in this scene as the officer flips the script on the VIP and gets information out of him. Again, I don’t think that sex, sexuality, or nudity should be automatically portrayed as bad or that these characters being bad should be conflated with them being sexual, but as before, it is interesting that the sex in the show is not automatically a good or necessary thing either. From my own point of view, I also find it noteworthy that it’s something that doesn’t enter into the stories of the main players.

Something else I mentioned on my other blog is my own personal belief that a Western show would not have allowed this to be true of our main cast of characters. Although much of Squid Game is about the dark, serious, and horrifying world of the games, I can easily imagine a Western interpretation of the concept still introducing sex into the plot. For instance, I could easily see a Western show have the sex scene between those two antagonists be a sex scene between two of our protagonists instead, framing this as the thing that cements their willingness to work together, or a big emotional beat when one or both of them eventually dies. Instead, what this show gives us are our main characters connecting with each other in platonic ways. They form friendships based on shared experiences or genuine sympathy, and I believe this makes it all the more real and emotional when the game forces them to lose or even betray one another.

Additionally, the show doesn’t automatically rely on the

trope of these characters getting back to romantic interests. In fact, other

than Ali (the participant from Pakistan trying to provide for his family) and a

few side characters (such as an ill-fated married couple who join the games

together), none of the main characters are in current romantic relationships.

In Gi-hun’s case, he was married once, but his ex-wife has since moved on and

Gi-hun’s main focus for the games – in addition to paying off his debts –

is to provide for his daughter and his own mother, not a spouse or partner. The

same is true of Sae-byeok, who is completely focused on providing for her

mother and younger brother.

Like I said in my previous post, the fact that Sae-byeok

doesn’t have a romance waiting for her and doesn’t form one during the games is

incredibly refreshing, as is the fact that she’s allowed to be somewhat stoic

and play her emotions close to the vest without either of these things being

used against her. As someone who often talks about how media uses tropes and stereotypes

to shame and sometimes even force aspec and non-aspec characters alike into

relationships, these types of portrayals are extremely important. In that way,

they help the show be surprisingly aspec-friendly at times, even if it’s not

always aspec-accessible.

Speaking of which, an important thing I’d like to note: although

not shown, there are a few instances where sex is referenced or where sexual

language is used, including in some brief ways that might be considered

triggering, so I do advise caution and/or extra research before watching if you

feel these things might be a problem for you. For these reasons, I wouldn’t

describe Squid Game as being completely friendly to someone as

sex-repulsed as I am, or someone for whom certain sexual situations are

triggers or otherwise unacceptable. But in other way, as I mentioned in the

previous paragraph, it actually offers us an interesting and thought-provoking opportunity

to consider how sex and sexuality are portrayed in many streaming shows, a

topic I talk about frequently.

In conclusion, although Squid Game isn’t your typical K-Drama and includes some very un-Korean drama type things, I hope my review helps to illustrate that it can be a good gateway into this media nevertheless. Although it is my sincerest hope – for obvious reasons – that K-Dramas don’t become more Westernized as their popularity grows, I don’t think Squid Game is necessarily too Westernized, nor do I think it’s “too mainstream” to be enjoyed. As I’ve stated in this review, there are several extremely valuable things in the show, and I hope these things continue into the show’s next season.

Furthermore, something you’ll learn as you follow this blog

– or if you read my main one – is that my opinions are exactly that: opinions.

No one made me the arbiter of good taste, nor did anyone appoint me as the lone

voice of aspec people. Indeed, my own comfort level, opinions, and aspec

analysis may differ dramatically from those of other aspec people, since there

is no universal aspec experience. As a sex-repulsed AroAce person coming to media with my own unique needs and wants, I tend to be

far less able to tolerate sex in media than many other people can, so take my

opinions with a big grain of salt. That being said, I hope my opinions have

been interesting and thought-provoking, and are a good first step into highlighting

what makes K-Dramas so unique, as well as why they’ve become so dear to me.

If you’ve been on the fence about starting Korean media and

have heard a lot of hype about Squid Game, maybe consider giving it a

try if you can. K-Dramas of all kinds are full of amazing characters,

incredible stories, and a depth of emotion I was sorely missing from the media

produced in my own country, and I’m forever grateful that I found my way to

K-Dramas thanks to this show as the gateway. And above all, I hope you’ll keep

reading my reviews and that perhaps I can introduce you to your own gateway to

better media – and maybe even recommend you a new favorite show.

Comments

Post a Comment